By Brenda Cassellius February 9th Washington Post at 1:08 p.m. EST

Brenda Cassellius is the superintendent of Boston Public Schools. She served previously as commissioner of education in Minnesota.

Last month, I returned to teaching in a classroom after two decades. As the superintendent of schools in Boston, I got a lot of media coverage for working as a fourth-grade substitute teacher at Nathan Hale Elementary School on a day when more than 1,000 Boston school employees called in sick. Yet I was just one of hundreds of district staffers who pitched in to help.Opinions to start the day, in your inbox. Sign up.

Like school districts and employers across industries, Boston Public Schools has faced intense staffing challenges for the better part of two years, challenges made worse by the pandemic.

Now, as we enter the pandemic’s third year, America’s public schools are at risk of defaulting on their moral obligation to millions of children. Teachers, aides, principals, bus drivers, school lunch workers, custodians and other school staff are leaving in droves or are out of service due to illness. A dearth of substitutes and backup workers means day-to-day decisions about whether a school can remain open are the norm.

In Boston, we have consistently had a 20 percent job-vacancy rate since the summer in our food and nutrition services department. We have been short more than 100 bus monitors and approximately 30 bus drivers on any given day. And that’s in addition to teacher and other staff absences that can erode children’s learning experiences. The pandemic has accelerated our staffing challenges, but this concerning trend has been at our doorstep for the better part of a decade. Fewer recent college graduates are choosing teaching, and a 2021 survey showed that nearly one-third of America’s teachers were thinking about leaving teaching earlier than they’d planned.

Once seen as a stable career that came with the potential to make a significant positive impact on a community, teaching can no longer compete with positions offering more flexibility and higher pay. We need solutions to school staffing that go beyond what any one city or state can provide. Our state and federal government partners must work with us.

The road map to ensuring academic recovery and a return to stability for our students must include plans for modernizing neglected schools. We need funding forexpensive HVAC systems. Some outdated buildings should be torn downand rebuilt. We must also provide significant resources to confront the urgent mental health crisis our students face — they have unfairly carried an outsize burden these past two years.

There are additional common-sense steps we can take to address the critical shortage of teachers if we put our heads together, listen to the best ideas and muster the political will. First, to avoid a mass exodus of exhausted educators, we must offer retention bonuses that reward educators for staying in public schools. America’s teachers have weathered some of the worst of the logistical and cultural battles of covid-19, and they’ve earned this recognition. Retention bonuses would also help build a deeper bench of young teachers.

We need to recognize that choosing a career in teaching is as important as joining the military; both are critical to our national security and economic sustainability. We should offer free college tuition to students who commit to public education careers and loan forgiveness to current teachers who remain in the profession for 10 years. Let’s also set a national minimum starting salary for teachers of $75,000 per year. And let’s eliminate fees for teacher’s licenses, tests and fingerprinting.

Beyond that, the federal Education Department should create a national teacher licensing system. Suchlicensing would help create uniformly high standards from state to state and allow teachers to easily transfer their credentials when they move. And, as we ramp up our efforts to rebuild our teaching corps, we should create incentives to welcome back recently retired teachers who can fill gaps without reducing their pensions.

Let’s not forget the teaching aides who help to ensure our students get the individual attention and guidance they need. These roles will be critical in a time of recovery. Establishing an AmeriCorps program for college students or recent grads to become teaching assistants or aides in exchange for tuition reimbursement would be a huge benefit to our teachers and students.

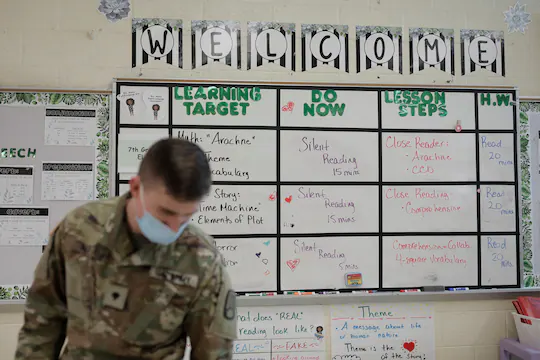

Finally, we should train and license our service members to drive school buses. While Massachusetts offered its National Guard to help school districts with transportation challenges, Guard members had licenses to drive vans only. We need bus drivers. Let’s learn and grow from this opportunity and incorporate large-vehicle training as part of their military training. This seems like an easy win.

Our teachers and other staff need help, but most important, our students are depending on us. They get one chance for a solid education. For their sake, we must map a way forward that draws more people to education careers and keeps good teachers in the classroom.1902 CommentsGift Article