Remote school was devastating for many students. In Richmond, Virginia, a plan to switch to a year-round calendar brought promise and pushback.

By Alec MacGillisJune 19, 2023 New Yorker

Angela Wright became the principal of Fairfield Court Elementary School, in Richmond, Virginia, in the fall of 2020, but she didn’t meet her students until a year later. At the start of the pandemic, Richmond had moved all of its twenty-two thousand students to remote learning. By the time they returned to the classroom, in September, 2021, after every other school district in the state, it had been eighteen months since they’d been inside a school building.

For Wright, the posting at Fairfield Court was the culmination of a steady rise: from instructional assistant to teacher to assistant principal to principal. When her father saw her first monthly paycheck as a teacher, he asked, “Is this for a week?” “He said, ‘Are you sure this is what you want to do?’ ” she recalled. “I said, ‘Yes.’ When you see kids light up, when you see that they get it, when you see kids who were tier three or lower rise to the top . . .”

Wright had previously been a principal in a rural school district, but after arriving in the Richmond system she settled for being an assistant principal for a few years. “Coming into an urban school district, I wanted to step back and take a look at their structure, their processes,” she said. Now she was eager to tackle the challenges facing the student body, which was almost entirely Black. Many of the students lived in an adjoining public-housing development, also called Fairfield Court. But Wright, in her first year, could offer guidance only at a remove. She dropped in on virtual classrooms, where students logged on from their beds or from crowded kitchen tables; often, they were not able to log on at all, because the concrete walls of their home interfered with a Wi-Fi signal. “Sometimes it was just, ‘Oh, it’s not working today,’ ” she told me.

When the students returned to the school building, Wright found that their needs were far greater than she could have imagined. Research released by Harvard and Stanford last fall found that Richmond’s fourth through eighth graders had lost two full years of ground in math and nearly a year and a half in reading. Even more apparent was their difficulty with basic interactions—fifth graders hadn’t been in person since third grade; second graders, since kindergarten. “Socialization with each other was huge. How to be around each other—those are building blocks for ages six to ten,” Wright said. “There was a whole retraining—what does it look like when you and another student disagree? They had missed that, not being in the building.”

Richmond is a particularly stark example of what education researchers say is a nationwide crisis. Student learning across the country, as measured by many assessments, has stalled to an unprecedented degree. Researchers have pointed to a number of causes, including the trauma experienced by children who lost family members to covid, but the data generally show that the shortcomings are the greatest in districts that were slowest to reopen schools. They also show that the falloff was far greater among Black and Hispanic students than among whites and Asians, expanding disparities that had been gradually shrinking in recent decades. “This cohort of students is going to be punished throughout their lifetime,” Eric Hanushek, an economist at Stanford, said, at a conference in Arlington, Virginia, in February. He presented findings demonstrating that the economic consequences of pandemic-related learning loss could be far greater than those of the Great Recession.

The federal government has sent schools a hundred and ninety billion dollars in pandemic-recovery funds, and districts are using some of that money for a range of interventions—intensive tutoring, expanded summer school, and after-school programs—though they have been hampered by the shortage of teachers and tutors. Even before the pandemic, Fairfield Court and other schools in the East End of Richmond, which has high levels of poverty, had received additional resources for social workers and for math and reading coaches; the new federal funding was used to provide an extended-day program three days a week for about forty kids. Wright appreciated the support, but she could see that more would be needed to make up the lost ground.

In Richmond, as in many other districts, the learning-loss debate has centered on time: the greatest challenge is finding extra hours for supplementary instruction. In early 2021, as it became clear that Richmond was not going to reopen its schools that spring, Jason Kamras, the superintendent of schools, shared in online forums the rudiments of a possible remedy: switching to a year-round calendar, with summer vacation limited to July, and four two-week breaks during the school year. Most students would still have a hundred and eighty school days a year, but the district would select five thousand students to receive up to forty days of extra instruction during the breaks. Teachers who volunteered to work would be paid more.

Kamras cited a report issued by staff of the Virginia legislature which indicated that, according to recent research, a year-round calendar produced varied results over all but had clear benefits for Black students. Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology at Duke, who has researched the issue, told me that, though most students suffer from a “summer slide” in math, losses in reading are bigger for students from low-income families, possibly because wealthier kids are more likely to have books around at home. He said that it made sense for districts to rethink summer break, which was a vestige of a more agricultural era and longer than in peer nations. “Our school calendar now is out of synch with the way most Americans live,” he said.

Wright, a fifty-seven-year-old Black woman, was in favor of the plan. “Having those kids start instruction early, we can get those kids to really feel good about themselves,” she said. “We need to have them here in the building.”

Richmond’s school board has been elected by voters since 1994, two years after Virginia became the last state to allow for direct election, rather than appointment, of board members, a system that now prevails in nearly all of the nation’s thirteen thousand school districts. In recent years, in Florida and elsewhere, school boards have attracted attention for culture-war skirmishes over book choices and instruction about gender and sexuality, but most of them labor in relative obscurity. Supporters of elected school boards see them as safeguards of citizen input into how taxpayer dollars are spent and how children are taught, an exceptional feature of U.S. public education which embodies the principle of local control; detractors view them as bastions of dysfunction, captured by interest groups or lacking the expertise to make decisions about pedagogy. In Richmond, the board’s nine members receive an annual stipend of ten thousand dollars; the chair, who is elected by the board, gets an extra thousand dollars. Meetings are held twice a month, at 6 p.m., and they often run until close to midnight, at which point public attendance, typically sparse to begin with, has dwindled to virtually nothing.

Stephanie Rizzi ran for the board in the fall of 2020. Growing up, she had bounced between her grandmother in Richmond and her mother, in Caroline County, north of the city. “I grew up poor and hungry,” Rizzi said. “I can remember being thirsty, not having access to water.” Her solace came at school. “My teachers saved my life,” she said. She attended Virginia Commonwealth University, in Richmond, and went into education. (She is now an administrator at V.C.U.) She taught English in three counties, all the while trying to get a position in the Richmond schools, which her children attended. After being unable to get hired by the district, she decided to run for the board that oversaw it.

Among those whom she joined was Kenya Gibson. Gibson had lived in Richmond before attending graduate school in architecture at Yale; she moved back in the late two-thousands, for a job designing retail stores. She joined a local effort that was fighting for more school funding and became vice-president of the PTA at her daughter’s school. When her local board seat came open in 2017, she ran for it, winning against an interim appointee who was backed by Mayor Levar Stoney and other “corporate Democrats,” as Gibson came to call various politicians and business leaders, some of whom had pushed in vain to switch the city to an appointed school board, in the mid-two thousands. “It’s about allowing the community to have a seat at the table,” she told me. “Not having a democratically elected school board is a scary notion.”

Seven of the board’s nine members were Black. One of the two white members, Jonathan Young—also the only man on the board—had long been in favor of switching to a year-round calendar. Young, a faculty administrator at Virginia State University, a historically Black institution, exuded an ornery independence, striking a critical stance against Kamras even as he often sided with his administration in disputes with other members. “To be quite blunt, we’re doing everything wrong,” Young told me. “It’s important to be able to say that the patient needs amputation, not just surgery.”

After Kamras unveiled the proposed calendar, hundreds of comments were submitted to the district’s online portal. At the March 15, 2021, board meeting, which was held online, Kamras’s chief of staff, Michelle Hudacsko, spent two hours reading the comments aloud. Many parents and some teachers expressed their support for the new calendar as a needed response to the pandemic closures. Meghann Kennedy, a parent, said, “It would be so beneficial for our kids, who have lost so much time.”

Other parents and teachers expressed opposition. Some cited practical concerns, such as the fact that they had already planned trips, camps, or second jobs for the summer. But the overriding argument was that, after the pandemic’s upheaval, the district shouldn’t add disruption. “What students need most this summer is normalcy—time to reach out to family they’ve missed, time to breathe,” a teacher named Amy Brown said. “Asking more than that of teachers and kiddos is nonsense.” Shannon Dowling, a parent, said, “Our teachers have experienced trauma—they are running on fumes right now. Our families have experienced trauma. We need a break.”

After the comment session was over, Tracy Epp, the district’s chief academic officer, reminded the board just how dire the educational setback was shaping up to be. She presented the latest data on early-elementary students, which showed a large increase in the number of children who were considered at high risk of struggling to read, especially among Black and economically disadvantaged students. More than half of all first graders were at risk, up fourteen points from the previous year. “The science is clear about what it takes,” Epp said. “There’s a lot we can do during the school day, but, when we look at fifty per cent not being on track, we’ve got to find more time to tackle these literacy issues.”

“If this doesn’t alarm everyone in the city of Richmond, I don’t know what will,” Young, the male board member, said. “If this data doesn’t say that a business-as-usual calendar is inadequate, then I don’t know what would.” Several of his colleagues also expressed dismay.

Others were more sanguine. Rizzi, the former schoolteacher, said that perhaps the district needed to help parents do more at home to teach reading. “There are some small things they could do to support their kids,” she said. “This doesn’t mean kids need to be in class forever.” Gibson, the former PTA leader, cited the opposition voiced by teachers and parents, and suggested that the district instead put the money toward improving summer school in 2022: “We owe the public to say, ‘We heard you.’ ”

The meeting had been going for almost five hours. Kamras was rubbing his eyes. Finally, he suggested that, if the board wasn’t ready to switch to a year-round calendar for the coming school year, it could resolve to do so for the 2022-23 school year. “Let’s put a stake in the ground,” he said. “We have a reading crisis that is going to impact our students for the rest of their lives unless we deal with it.”

The board approved the idea, with Young the only holdout. “Congratulations, everyone,” the chairwoman, Cheryl Burke, said. “We’re going to have a traditional calendar for this school year, and then move into the 2022-23 year with added changes for year-round.”

Kamras had spent a summer during college working as a tutor in a housing development in Sacramento, his home town. He came away from the experience with two insights: that he really liked working with kids, and, he said, that “the third and fourth graders I was working with were every bit as capable as any other kids I’d been with, but had clearly not had the same opportunities that I’d had—and that just struck me as wrong.”

He joined Teach for America after college and started out as a middle-school math teacher in Washington, D.C. In 2005, he was named National Teacher of the Year, and shortly afterward he joined the administration of D.C.’s schools chancellor at the time, Michelle Rhee, in a role focussed on teacher recruitment and retention. In three years as chancellor, Rhee presided over rises in test scores while clashing with the teachers’ union over her efforts to cull underperforming educators.

Across the nation, the two-thousands showed steady gains for students, as measured by such tests as the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Notably, the achievement gap between Black and white students narrowed. “It’s useful to remind people that things before the pandemic were improving,” Thomas Kane, an economist at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, told me. “We had been making progress.”

Kamras became superintendent of Richmond’s schools in early 2018. The district faced challenges. For one thing, many families did not enroll their kids in its schools. The city has roughly equal shares of Black and white residents, but its public-school enrollment is sixty per cent Black, twenty-five per cent Hispanic, and ten per cent white. Still, Kamras noticed that many people who had attended Richmond Public Schools and sent their children there felt a great sense of ownership. “I was struck by how much pride there is in R.P.S.,” he told me. “It’s the engine of mobility for so many people here in the city.”

Before the pandemic, Kamras had been skeptical about a year-round calendar, but he was alarmed by the effects of virtual learning. “Three decades of gains were wiped out,” he said. “You’ll hear this now from elected leaders and others: ‘Stop talking about the pandemic, you can’t blame everything on the pandemic.’ I am most certainly not, but to ignore the impact of the pandemic and the fact that it’s going to have repercussions for years would be tantamount to sticking our heads in the ground.”

He began to see year-round school in a new light. For one thing, it seemed more workable than adding hours to the school day, given how drained many teachers felt at dismissal time. And it avoided the drawbacks of a long break for struggling students. Kane, at Harvard, noted that traditional summer school is often insufficient, because it’s typically voluntary and plagued by low attendance rates. Although paying teachers and staff for additional weeks of work was an added expense, extending the year was logistically easier than other supplements, such as hiring a whole new corps of outside tutors. “We already have the school buildings and the teachers,” Kane said.

“I shifted and said, ‘There may not be any better time than now to rip the Band-Aid off,’ ” Kamras told me. “No, it may not be perfect, but we’re going to be dealing with the impact of the closure for years to come.”

But, in the fall of 2021, some members of the school board started wavering about the year-round calendar. On November 15th, Kamras presented to the board several options—one with the same number of school days as the status quo, plus extra days for certain students, and others with ten extra days for all students. The most expansive option would cost roughly thirteen million dollars a year in additional pay for teachers and staff, to come from the district’s federal recovery funds. The plan was to hold a public survey on the options.

Kamras was taken aback when several board members declared that the survey should have another option, too: the status quo. Gibson said that changing the calendar would spur teachers to quit, and that it was unfair to students. “We’re basically merging school into a full-time job,” she said. “It’s not right that Black and brown students in our district are chained to their desks essentially further into the school year while their counterparts in the counties get to play and have a summer.”

Kamras noted that the calendar would still have a six-week summer break, but several members were unmoved. “I wonder if there’s a way to address summer learning loss without adding days or going to year-round,” Rizzi said. “Is there some kind of way that we can take a creative approach and try something that isn’t going to feel like an extra job for our parents and our children?”

Kamras replied that he was simply following the directive of the board’s vote for a year-round calendar. He spoke with the tone of forced agreeableness that often characterized his contentious exchanges with the board. “I do believe that coming out of the pandemic we do owe our students more,” he said. “I do believe this is the right direction for this school division to go. I do believe this was what I was directed to do by the board.”

The survey went out with the status quo as an option, and it received the most votes, with higher support from white families than from Black ones. Kamras presented the results on January 10, 2022, in the midst of another challenge: keeping schools open during the Omicron wave. A week later, he proposed a traditional calendar for the coming year.ADVERTISEMENT

Young was the only board member to vote against the traditional calendar. “This board, when it punted on an alternative to the status quo, said that we would adopt it for the next school year,” he said. “That, I presume, did not mean anything when it was said.”

Recently, I asked Rizzi, who is now the chair of the board, about the change, and she said that her vote in the spring of 2021 was not to approve a year-round calendar but simply to study it further. She had doubted that it would actually happen, given resistance from teachers and their union, the Richmond Education Association. “I knew that the R.E.A. was mobilizing against it, and that there was going to be a lot of pushback, and teachers wouldn’t want it,” she said. “It wasn’t that we would definitely support it next year, it was that we would return to discuss it.”

Across the country, other school districts were also grappling with how to add more instructional time. Atlanta added thirty minutes to the school day. Los Angeles added four days to the school year, which it said would be optional for both students and teachers, with extra pay for teachers who took part; the teachers’ union objected, saying that it fell outside their contract agreement, and participation by students ended up being very low. Dallas had more success: it gave schools the option of adding up to twenty-one days for selected students, and forty-one schools, roughly one in eight, decided to do so. Five others opted for an extended-year calendar for the whole school. Hopewell, which is half an hour south of Richmond and has a majority-Black student population of slightly more than four thousand, became the first district in the state to institute a sweeping year-round calendar, in 2021. In Dallas, the schools with the added days showed slightly larger learning gains; Hopewell has reported lower rates of teacher turnover now that there are more breaks throughout the year.

Other districts have gone in the opposite direction: cutting down on classroom time in the name of safeguarding student and staff mental health, an explicit priority of some of the federal funding. Spokane, for example, reduced students’ classroom time partly to give teachers more time for professional development. Marguerite Roza, a Georgetown University research professor of education policy, was sharply critical of this approach. “How can you believe that less school is an intervention for learning recovery?” she said. “You can’t imagine that less school is the remedy for having all that learning interruption. The kids aren’t even there.”

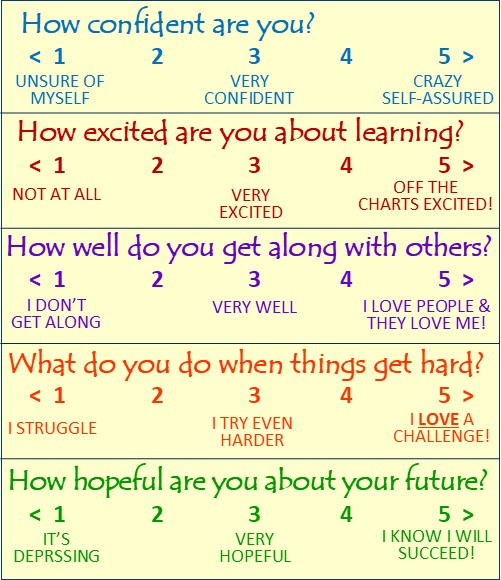

Dan Goldhaber, the director of the Center for Education Data & Research at the University of Washington, told me that one challenge to building support for added instructional time is that parents and other community members are not always aware of just how steep the drop-off has been, in part because many schools have been grading more leniently in recognition of the pandemic’s challenges. “There’s a real urgency gap,” he said. “It’s asymmetry between what we can see empirically about where kids are and what parents think, based on opinion surveys. There’s the belief that kids are doing O.K., and the desire to snap back to normal. And that’s problematic, because normal seems to have gotten us back to the pre-pandemic pace of test-score growth, but the pre-pandemic pace does not make up for the pandemic, and we need to be on a much higher trajectory.” An analysis of data from about eighty per cent of public schools in the country has found that, in districts that went remote for ninety per cent or more of 2020-21, the decline in math scores represented the loss of two-thirds of a year, nearly double the drop in districts that were remote for less than ten per cent of the year. And these numbers don’t take into account the millions of students who have vanished from the rolls entirely since the extended hiatus during which the norm of attending school eroded.

Roza detected a more depressing factor contributing to the urgency gap: people have simply grown inured to talk of underachieving schools. “The system has always had some kids failing, and now we have more,” she said. “There’s maybe a numbness to it.”

Recently, I spoke with a newly elected member of the executive board of the Richmond teachers’ union, Melvin Hostman, who said that it was hard to agree to Kamras’s push for additional instructional time when there were so many other problems that needed to be addressed: lack of toilet paper, school buses arriving late, and widespread absenteeism among them. He added, “The whole thing about learning loss I found funny is that, if everyone was out of school, and everyone had learning loss, then aren’t we all equal? We all have a deficit.” When I noted data showing that the loss had had racially disproportionate impacts, he said, “Of course—because our society is inherently unequal.”

Hostman, who is in his sixth year of teaching high-school history, said that what bothered him and his colleagues was that the pandemic had laid bare how much in society had been broken for a long time, making it possible to reorder things in a dramatic way: “Now people are saying, ‘We’re going back to the way things were before.’ But we didn’t like the way things were before.” He didn’t see extending the school year as a new approach: “They’re taking the weird policymaker position that what we’re doing isn’t working, so we need to do more of it.” He offered additional insight into why teachers were suffering low morale now that they were back in the building. As hard as remote learning was, he said, “there are many teachers who feel like the only time they had a work-life balance acceptable to them was during virtual school.” Teachers had been able to work from home, and many districts had cut back class hours to reduce screen time, giving teachers more flexibility to run errands, exercise, and walk their dogs, just like other professionals doing remote work.

Now teachers were back in school daily, still cramming in class prep during their few empty periods, still bringing a lot of work home at night while many of their professional peers were enjoying hybrid schedules. “An industry that functions only because of additional labor that’s unpaid is trying to get people to return to that,” Hostman said. “And it’s difficult.”

Ayear after the defeat of the year-round calendar, Kamras decided to try again. His relations with the board had grown increasingly strained: In August, 2022, after the latest state test scores showed the district doing even worse in math and science than it had the year before, there was speculation that the board might vote to fire him. Mayor Stoney, who is Black, had strongly backed year-round school, and he urged the board not to act rashly, saying that firing Kamras just before the start of the school year would be “catastrophic.” “No one should be surprised that prolonged virtual learning and the trauma of the pandemic would negatively impact academic outcomes,” he tweeted. “It’s why Superintendent @JasonKamras wisely proposed a year-round academic calendar. The School Board dismissed his proposal.”

This time, Kamras moved more incrementally. At a meeting this January, he told principals that he was launching a pilot program in which a few schools could adopt an extended calendar, adding twenty days by ending summer vacation in late July.

Under the terms of the pilot, which emerged a few weeks later, teachers at participating schools would receive a ten-thousand-dollar bonus and some additional salary, plus five thousand dollars more if their school attained certain metrics. The total cost would be a little more than a million dollars per school. A school could participate only if it had strong support from staff and parents. Kamras invited principals to apply; he would then winnow the list of candidates to a handful, after which principals would survey their school community to gauge receptiveness.

Angela Wright seized on the idea. The social dislocations from the pandemic were still pervasive, and included heightened levels of violence in and around the city’s schools, and frequent alerts from a monitoring system on students’ laptops that was used to detect threats to other students or to themselves. In mid-October, a seventeen-year-old boy was found in a garbage can in the Fairfield Court housing development, fatally shot. “There maybe are some schools that don’t need those twenty days,” Wright told me. “But we know that, for some of our kids, having that whole summer out—it would have been better if they had been in a safe learning environment, so they can prosper.”

Allison El Koubi, the principal at Westover Hills Elementary, south of the James River, was also interested. Westover Hills had a lower rate of student poverty than Fairfield Court did, but it, too, had suffered steep drop-offs in achievement, in addition to a brush with violence: in October, a woman had been fatally shot during an altercation just outside the school shortly before afternoon dismissal; a teen-ager was later charged with the killing.

Like Wright, El Koubi saw the pilot program as an opportunity to build stability. “We had this huge disruption, we’re seeing increased levels of trauma in students and more need for social-emotional learning, and there’s not enough time,” she told me. “Students with additional challenges can learn the same amount in a year as their higher-income peers, but they tend to lose more in the summer, and that gap just keeps widening every year.” She also saw the pilot as a way for teachers to earn more money. “When I heard about how much the increase in salary or bonus would be, I thought, This is too big a decision to make on my own,” she said. “I want our staff to have a possibility to weigh in on it.”

Both principals applied for the pilot. Wright began gradually building support with her staff, but El Koubi, under the impression that principals weren’t supposed to publicize the proposal until Kamras settled on a list of candidates, held off.

On January 31st, the local CBS affiliate, WTVR, reported that Kamras had chosen four candidates for the pilot, including Fairfield Court and Westover Hills. The news caught teachers and staff at Westover Hills off guard, and many of them recoiled from the idea. In a straw poll conducted two days later, only thirty-seven per cent of employees said that they were interested in learning more about the pilot. “When it came out in such a jarring way, that created a lot of strong feelings about it immediately,” El Koubi said. “It felt like it was just too much.” She removed the school from the pilot. One teacher told me, “The thought is good—that we’re trying to combat whatever we lose from the students being gone so long in the summer—but the idea being brought so quickly was a tad bit too hasty.” He went on, “When you’re told that you have to work harder when you already work as hard as you possibly can, day to day, it’s not necessarily what you want to hear.”ADVERTISEMENT

At Fairfield Court, Wright charged ahead. She held a string of sessions with small groups of teachers and staff to explain the program. Together, the educators looked at the data showing the drop-off that kids had suffered during the summer of 2022, losing much of what they had gained the prior year, and started imagining better outcomes. It was “everybody believing in the same dream that we needed to move kids to the next level,” Wright said. “We all have to believe in our kids—that we can be successful in doing this.” All but two staff members voted for the pilot, so she was able to start surveying parents.

Wright also needed support from the school board, which would get a final say on the pilot. On February 6th, Giordana Buffo, a teacher at Fairfield Court, came to a board meeting to testify on behalf of the proposal. “Yes, this extended school year will come with some challenges for me personally, as well as many other teachers,” she said. “But, in the end, I feel like it would be beneficial to the academic success of our students, and help mitigate some of the learning loss that many of our students face when they’re not in school for an extended period of time.”

Wright spoke a few minutes later, praising Fairfield Court as the “hidden gem in the East End.” She told the board about the data showing that the gains her students make during the year are often lost over the summer. “When we create the opportunity for underprivileged scholars to overcome disadvantages and find success, it levels the playing field,” she said.

The next speaker was Anne Forrester, a middle-school teacher on the union’s collective-bargaining team, who, a couple of months later, was elected chapter vice-president. She warned the board that the pilot might be “wasted money.” “This proposal for a two-hundred-day calendar, it might work, sure,” she said. “But, to me, it doesn’t make sense to do that until we’ve gotten our schools up to where they need to be. You’re putting an addition on a house that has a leaky roof.”

One Tuesday in late February, I visited the Fairfield Court housing development. A few days earlier, the district had announced that schools would be closed that day, to align with surrounding suburban counties that were closing for a special congressional election. The day before had been Presidents’ Day, making for an unexpected four-day weekend. It was warm, and kids were milling around on the stoops and in the courtyards of the development, a collection of well-worn two-story brick buildings.

The mothers and grandmothers whom I spoke with were in favor of a year-round calendar and the two-hundred-day pilot, casting it in terms of common sense: kids had lost a lot during the pandemic, their summer break was longer than in much of the rest of the world, and they didn’t have enough to do during it. “Other countries don’t do it the way we do it, and we’re consistently falling back on our education,” Octavia Bell, whose three daughters were in middle and high school, said. “You don’t have to reinvent the wheel if you see something working somewhere else.”

I spoke with several women on the next block who among them had about a dozen grandchildren in city schools. When I asked about the argument, made by some parents, that the shorter summer break would interfere with family trips, they scoffed, saying that few people in Fairfield Court could afford to go anywhere. Other parents “are too busy worrying about what they’re going to do when the kids are in school,” Diane Hicks-Taylor said. “ ‘Well, I had plans, I wanted to do this and do that.’ No, let the kids go to school!”

When it came time for Wright to survey Fairfield Court parents, she approached the task like an election campaign, reaching out to parents anywhere she could: at a coffee hour outside school, at an awards ceremony, at a soul-food lunch. She had staff call the parents who still hadn’t voted. In the end, ninety per cent of families voted in favor of the two-hundred-day pilot. The twenty-one remaining families were told that they would be able to transfer to another school if they wanted.

On March 6th, Wright came back before the board to tell its members about the survey results and watch them vote on the pilot. Kenya Gibson, the former PTA leader, said that she opposed it, because she wasn’t sure how it would be funded after the federal money ran out. Kamras replied that, if the pilot showed success, the city could seek funding from the state or other sources to expand it.

Only two members voted no: Gibson and a woman named Mariah White. After two years of efforts to expand instructional time, the board had finally approved such a move for one of its fifty-four schools. Two weeks later, the board approved the pilot for Cardinal Elementary, which has a heavily Spanish-speaking population. This time, Rizzi voted against it, saying that she shared Gibson’s concerns about whether the bonuses for teachers at the pilot schools violated their collective-bargaining agreement. The fourth of Kamras’s original candidate schools, Overby-Sheppard Elementary, was deemed to have insufficient family support.

All told, only about a thousand of the district’s twenty-two thousand students will return to school in late July.

After the votes, Rizzi elaborated on her resistance. “ ‘Learning loss’ is largely a subjective term,” she told me. “Working to standardize our kids at any point in their learning process is an artificial exercise. So we experienced this pandemic, and some of our students aren’t performing as well from a standardized perspective. Characterizing it as learning loss looks at it from a deficit perspective. We should be looking at it as where we are now, and go from there.”

The day after the vote on the Fairfield Court pilot, I got a tour from Wright. The school was a hive of activity, and a reminder of how much beyond academic instruction is provided by many schools: in one room, children were getting free eyeglasses; another group was off at a pool having free swim lessons. In a kindergarten classroom, a teacher was helping her students to count to a hundred, while, in the hallway outside, a reading coach was huddled with some second graders who had been pulled out for extra help.

In her office, Wright talked excitedly about the school’s detailed plans for the extra twenty days, which will begin on July 24th. “This is not just about growth, it’s about accelerating to the next level,” she said. “We want students to be a hundred-per-cent proficient. We want kids to continue pushing through the ceiling.”

Later, I visited Westover Hills, where Allison El Koubi told me about the things that she had hoped to accomplish during the pilot. The next day, she informed her staff that she was leaving her job as principal at the end of the year. Her departure would prove unexpectedly abrupt: On June 6th, a shooting outside the graduation ceremony for one of the city’s high schools killed a graduate and his stepfather, and wounded five other people; police arrested a nineteen-year-old man. The district closed schools for the remainder of the week, ending the year several days early.

After speaking with El Koubi, I asked parents picking up their kids if they had been disappointed that the pilot hadn’t proceeded. One mother, Alanna Scott, said she hadn’t really seen the point of extending the year to make up for what children lost in the pandemic. “It’s past now,” she said. “Whatever they know, they should keep rolling with it. The kids don’t know what they missed.” ♦

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.Published in the print edition of the June 26, 2023, issue, with the headline “The Pandemic Generation.”

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/06/26/what-can-we-do-about-pandemic-related-learning-loss