Social Emotional Learning aka (SEL) is more than a fad. It comes from the awareness that what students learn about themselves is just as important as what they learn about any other subject. Why is it that schools rarely have time to teach students how to better know themselves?

COVID has left the curriculum in tatters. Tests show students are behind. Most schools are teaching to “Catch Up.” Teachers have no time to ask students how they are feeling. What if they are overwhelmed? What if they are depressed? What if learning is the last thing on their minds?

Yet, ask any struggling teacher. They will know what students are saying, in the only way kids can speak- through bad behavior. “We are not ready to learn”-they are saying- “until you are ready to learn from us and where we are, and what we have been through.” One million plus dead, school suspended for over a year, Internet Interrupt Zoom School, and you presume we are ready to learn? That all is back to normal for us? Why won’t you listen? Don’t we have any say?

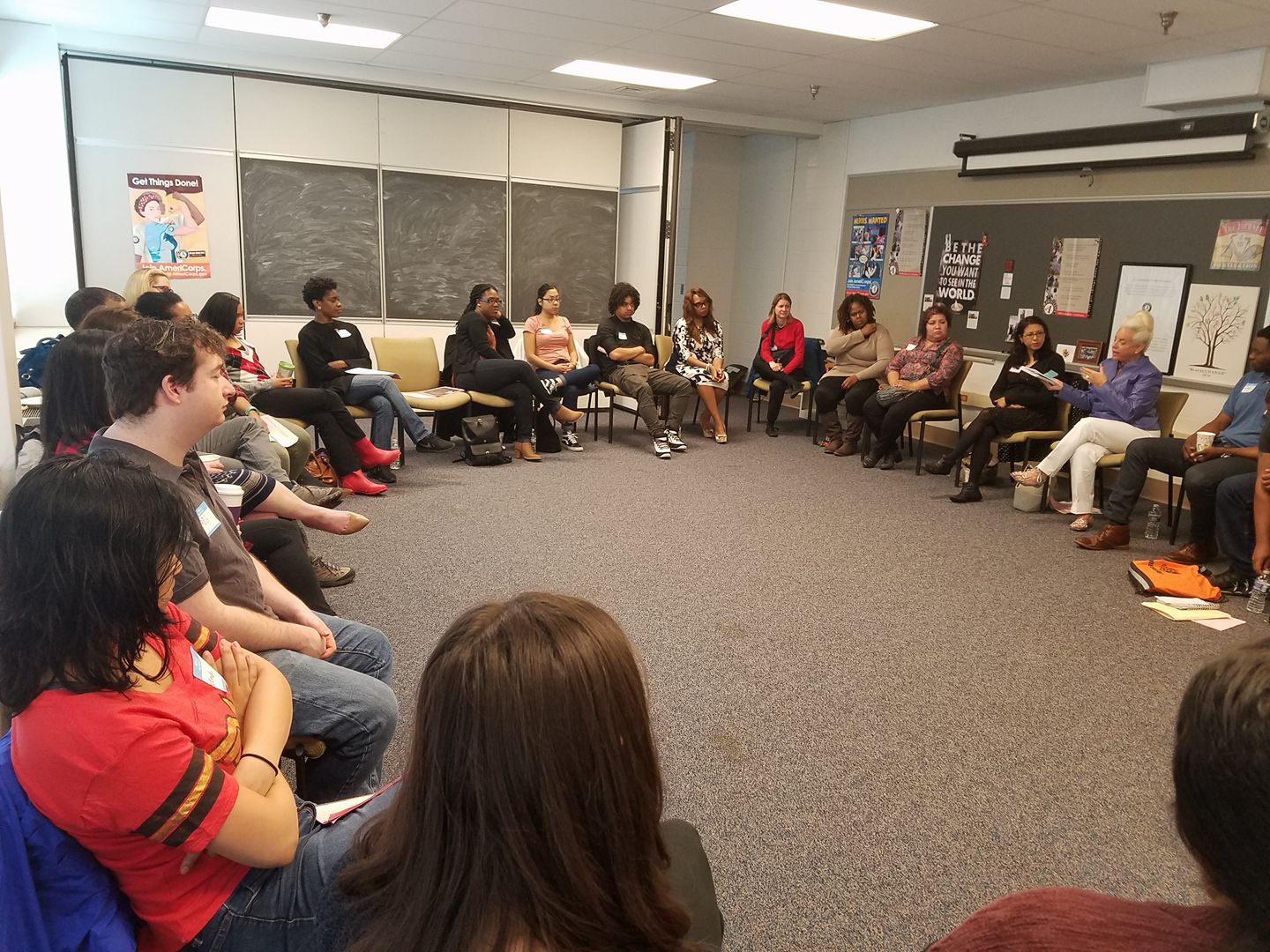

SERVING WITH AMERICORPS

AmeriCorps Project CHANGE is recruiting a ‘Champions of Student Success’ team of inspired members who sign on for a year to change all this. Through the innovative yet simple SEL instrument MyScore that Project CHANGE has developed, AmeriCorps is striving to bring the students back into the conversation about their lives. That, after all, is the one area in which they are the unrivalled experts.

Standardized tests want to know if you can write and read, (That is TheirScore) but we are interested in ‘How Confident, How Curious, How Collaborative, How Courageous, How Career and Future- focused you are- (That is MyScore.) These 5C’s are just as predictive of becoming a successful Life Learner as any test result.

We know which students are struggling, because they tell us. We can support them to persevere and grow. We know which class is stuck because most students are telling us they are bored or struggling, or feel alone. We know which students are thriving and who to makes into allies to build a positive climate of inquiry in the classroom. They can assist their teacher with those classmates who might be behind. MyScore allows us to build an environment for learning and growing. It lifts up every voice.

This seems so obvious-to ask the kids- but it represents a radically different approach to student welfare. Their voice is given a priority. Project CHANGE wants to democratize education and, using SEL, re-center the curriculum on life, and on the self. These are life lessons worth learning. After the pandemic, it is time to reclaim the student voice as worthy of shaping the dialog of what schools might become. Parents and teachers or experts alone can’t be allowed to drown out the voice of the constituency we are there to serve.

WHO IS PROJECT CHANGE?

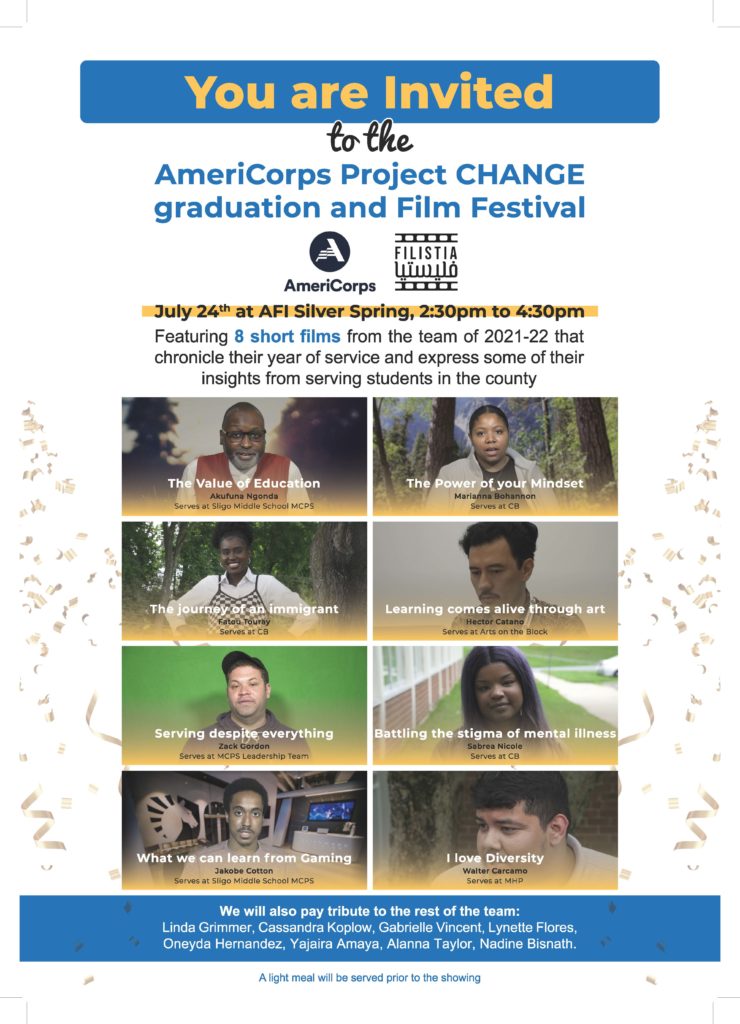

Project CHANGE is the original AmeriCorps program that for 21 years, has been serving Montgomery County students. Every year, in partnership with MCPS, we look at emerging student needs and search for ‘Champions of Student Success’ who have a servant’s heart and are ready and able to respond.

Project CHANGE’s unique Social Emotional Learning Approach is based on a narrative theory of change. Focusing on the story that a student is telling themselves about their value, their talents, their chances for success and their future, MyScore gets students to focus on growing in the 5Cs of confidence, curiosity, collaboration, courage and career-future focus. Members are trained to use this tool and shape interventions around the student’s emerging sense of self.

Imagine being the difference between a student passing or failing? Imagine being the difference between a student believing in herself and a student acting out their despair? Imagine helping a teacher or after-school program leader create the safety and the trust where children can thrive and feel the thrill of being alive.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

DO YOU QUALIFY?

Requirements for AmeriCorps members in Project Change:

1. 18 years of age

2. High School Diploma

3. Drivers license/access to a vehicle

4. Able to work in the USA

5. Able to devote 35 hours a week

6. Some experience working with children/youth

7. Willing to have a criminal background check

8. Show Proof of full vaccination status for COVID19

9 Able to serve for a full 12 months Late August 2022 – Mid August 2023

BENEFITS

In return, AmeriCorps members receive:

Professional Development weekly training on Fridays ( 150 hours)

$21,500 living stipend with possible bonus

Student Loan forgiveness for the year served

Child Care allowance for members who are parents

$6,450 educational scholarship upon completion

Health Insurance including vision and dental

Professional mentoring

Peer support network and connection to AmeriCorps alumni

Preference in hiring for many organizations

The positions offer an overall life-changing experience. Most positions are full-time (1700 hours during a 12-month term) beginning end of August 2022- August 2023 and some positions are half-time (900 hours during a 12-month term).

______________________

BACKGROUND

Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS) with 160,000 Students closed schools from March 2020- September 2021, leaving kids cut off from their peers, depriving them of normal healthy social outlets. School is back but how do we make up for their losses in Social/Emotional learning, the very skills students need most to succeed in life.

This is where YOU come in. Your role in the school will be as a mentor and coach to your peers, and to model for them ways to

-Actively engage and problem-solve physical, psychological, social and disciplinary issues that affect themselves and the community.

-Take responsibility for their actions.

-Set themselves up for success

If you are interested or need more information, please email

americorpsmontgomery@gmail.com