By Doris Iarovici December 18, 2021 at 9:00 a.m. EST

The first-year student in my office was terrified. Here he was, finally living on the campus of the college he had dreamed of attending, and instead of joy, he experienced an unsettling sense of unreality.FAQ: What to know about the omicron variant of the coronavirus

The world around him felt off; strange. Worse: He felt off, detached from himself. Too aware of everything he said and did, and at the same time, removed, not relating. The numbness and inability to connect had persisted over a couple of days, triggering panic.

How would he navigate the transition from high school to college if he could not connect? Was he losing his mind?

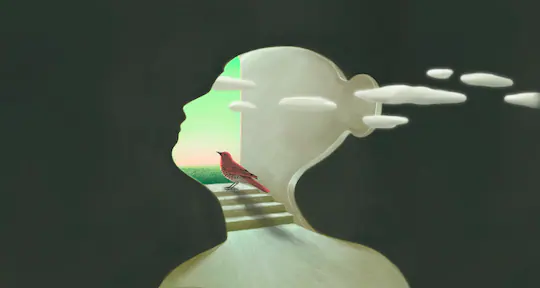

Derealization and depersonalization — the subjective experiences of unreality of either the outside world or of the self — are fairly common, usually transient phenomena. I am used to hearing about them from the young adults I treat as a college psychiatrist, although these complaints usually come up as side-notes rather than the presenting concern.

Campus celebration and covid fear: Colleges reopen for a second fall under the pandemic shadow

But the first week back in my campus office in Cambridge, Mass., this fall, after 18 months of virtual practice because of the pandemic, several students came to see me in crisis specifically because of these symptoms. I began to wonder if the return to school has upended our understanding of reality in new or particular ways.

Many of us have experienced brief moments where we feel as if we’re in a dream or in a fog or numb. We might feel disconnected from, or floating beside or above, our own body: too keenly aware of actions that normally happen without our consciousness. Usually this happens when we’re very tired or significantly stressed. It’s a frequent response to trauma. Alcohol, cannabis and other drugs can also be triggers.

But my patient was experiencing these feelings sober, just as he finally got to do something he’d wanted to do for a long time. I might have attributed his symptoms to the stress of starting college and leaving home for the first time, had I not also seen upper-class students with similar difficulties. One student who had navigated travel abroad during the pandemic — a particularly challenging task — felt especially disconnected upon return to the familiarity of campus.

As college campuses reopen, many faculty members worry about covid

Of course, campus is and is not familiar this year. As I walked across the main quad that first week back, the word “surreal” bubbled up in conversation after conversation among the undergraduates not sitting in my office. An editorial in the student newspaper described how watching the campus come alive again felt “like a dream.”

In an informal survey of my colleagues who work in college counseling centers nationwide, other clinicians agreed they had seen an increase in student complaints of depersonalization or derealization. Some had noticed this over the course of the pandemic, not just when most campuses reopened a few months ago. One psychiatrist commented that even pre-pandemic, she encountered these symptoms more frequently among college students than among adults in other settings where she had worked, such as in a clinic for people with chronic mental illness.

Although depersonalization and derealization can occur in a variety of psychiatric disorders, from the early stages of psychoses to depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and panic disorder, they’re quite common in the general population. Incidence decreases with age, and young people seem more susceptible. Although exact rates in college students are not known, surveys of students not in treatment for psychiatric conditions reported depersonalization or derealization experiences in 8 to 46 percent of respondents, depending on the method used.

In one pre-covid-19 study of over a thousand adults in rural North Carolina in 2001, nearly 1 in 4 reported depersonalization or derealization over the past year. The detachment from self more commonly occurred when people felt nervous or depressed, or after a severe stress. Derealization seemed more frequent when people felt they had experienced something dangerous.

Colleges prepare for unknowns with omicron variant

During the pandemic, we’ve all felt a sustained sense of danger. Most of the students now on campus have endured more than a year and a half in isolation, a particular challenge for adolescents and young adults. The normal fears about making friends and keeping up academically are accentuated. And uncertainty persists.Advertisement

Limited socializing is allowed now among vaccinated students, but there are so many rules and restrictions. People continue to get sick. New variants appear, triggering fears of endless cycles of isolation. Some students have lost family members or friends to the coronavirus, or have been sick themselves. Against this backdrop, it is unsurprising that more students might experience more intense dissociative symptoms.

And reality has been significantly altered for us all.

We’ve become accustomed to interacting online more than in person. For me, a sense of unreality was most acute when we went into lockdown last March: the experience of being cut off from everything usual in my life was disorienting. But my return to work on campus felt reassuringly normal, even with the strangeness of continued mask-wearing and other new protocols. In-person activities make up the bulk of my lived experience.Advertisement

For young adults, who were already spending more time online than we nondigital natives did, 18 months constitutes a bigger proportion of their lives. Perhaps this more firmly entrenches in their brain that virtual life is the norm. For some, then, live interactions become more jarring. And with the rise of extremely divisive discourse online, and disagreements over basic scientific truths, we are all bombarded with challenges to our shared understanding of reality.

Most people who experience depersonalization and derealization find that it improves within a few weeks, without professional intervention. The understanding that these are normal responses to significant stress, fatigue or some substances often helps symptoms fade.

One study showed improvement in patients instructed to direct their attention to the bodily sensation of breathing. In general, mindfulness meditation techniques help ground people experiencing dissociation.Advertisement

Distraction is also helpful, especially when it involves talking to or being around other people, instead of isolating. Labeling the feeling, and redirecting the attention to another activity, such as listening to music or exercising, can help.

My students improved rapidly with treatment, which included a combination of talk therapy and medicine. They told me they valued the opportunity to examine their strange experiences without fear that they would be labeled crazy. Should the symptoms continue, worsen or recur, other treatments can help.

In a time of unprecedented disruptions, the surreal has become commonplace.

Doris Iarovici is a psychiatrist at Harvard University and the author of “Mental Health Issues and the University Student.”