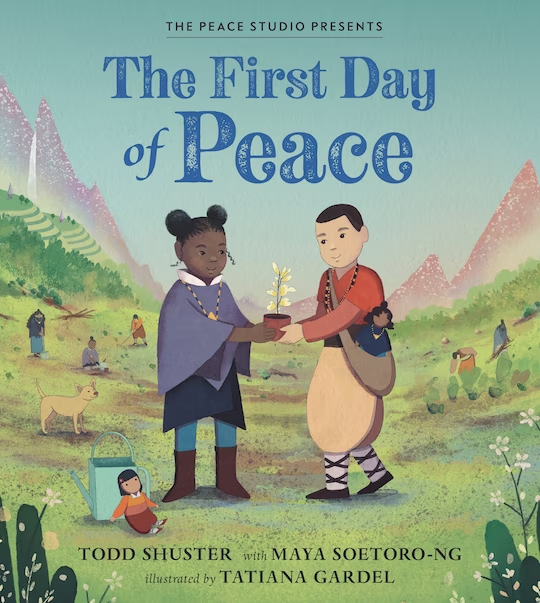

Maya Soetoro-Ng, professor, nonprofit founder and former president Barack Obama’s half sister, talks about her new children’s book, ‘The First Day of Peace,’ her life’s work and her mother’s influence on her efforts

The neighboring agrarian communities in the new children’s book “The First Day of Peace” are not at war. The mountain people stay atop their high ridges, drinking from the lake that flows below to quench the valley people. Neither share their crops, which dwindle as heat waves and heavy rain startle their land into vacuity, and they squabble at the border. Not at war but not quite at peace.

Until — “A wise and brave mountain girl said, ‘We need to help.’ From house to house, her idea spread. Love catches on.”

The idea that peacecan begin with the small actions of individuals and communities permeates the work of Maya Soetoro-Ng, a professor at the University of Hawaii, an activist, the half sister of former president Barack Obama and the co-author, with Todd Shuster, of “The First Day of Peace,” which will be released Sept. 21, the United Nations-declared International Day of Peace.

In 2019, Soetoro-Ng and Shuster founded the Peace Studio, a nonprofit group that trains storytellers in “conflict transformation,” or the construction of new narratives that combat the emotional and interpersonal impacts of a violent world. They wrote “The First Day of Peace” as part of that mission, hoping, as Soetoro-Ng notes in the book’s afterword, to encourage children to “imagine a better world and begin to make it real.”

We spoke recently with Soetoro-Ng, 53, who is also a programming adviser to the Obama Foundation, about storytelling as a tool for connection, the links between environmentalism and peace-building in the face of climate change, and how her mother’s work abroad influenced her life choices.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Q: Why did you set out to write “The First Day of Peace”?

A: So adults can speak to children about difficult topics like climate change and share the lessons of the book, namely that children are powerful, that you don’t have to be of a specific age to participate in a movement, helping others and working to better your community. Peace is something that we all have to commit to building with whatever resources, networks, ideas and creativity that we have, day after day and year after year. It’s not so much for children to explore on their own, but for adults to be facilitators of conversations that enable young people to think about their own capacity to help someone on the playground or to create peace in their own communities, to feel strong.

Q: The book links environmentalism and peace-building. How should we think about that connection in our own world?Share this articleShare

A: By 2050, nearly all of the world’s children, over 2 billion of them, will be exposed to extreme, frequent heat waves each year. We need to tell stories about the climate crisis that are not frightening but are empowering, and that enable us to think about what we can do to engage community solutions, especially in front-line communities, how young people can connect across their differences to help build social movements that allow for shared resources for circular economies rather than just hoarding resources. We need to think about the ways we can engage in mutual support and refamiliarize ourselves to nature and to one another to prevent the worst effects of the climate crisis. Communities that demonstrate positive peace-building repair more readily.Advertisement

Q: You also wrote the children’s book “Ladder to the Moon,” published in 2011. Do you see yourself writing more?

A: I’d love to. I don’t anticipate leaving my work as an educator, but this is one way that I would love to continue to bring pedagogical principles to young people embedded in stories. So I have a book that I’ve written. I’m just doing final edits on it. It’s a young adult novel called “Yellowwood.” It has a lot of the principles of positive peace-building and a philosophy of restorative justice and conflict transformation in there. Hopefully it’s not pedantic. Hopefully people like it and want to read it. But I always think that we learn best when we care about the characters and we feel empathy for their journeys. And storytelling is the best way to accomplish that. That creative connection that we can forge through narrative is such a beautiful thing, and I hope to be able to do that for the rest of my life.

Q: What is “Yellowwood” about?

A: It imagines a world and a girl who is in the in-between. She’s in liminal space. Her father comes from one culture and her mother from another. It uses a lot of the Hindu and Buddhist principles and stories of my childhood in Asia and weaves them in with a Western narrative construction. She’s a healer, and there’s some magic and young romance, and she endeavors to end a war. So she’s a peace builder.

Q: Was this taken from multicultural experiences in your own life, growing up in Indonesia and Hawaii?

A: I utilize a lot of the experiences and the images and stories of my childhood in Indonesia, and I think that Indonesia gave me a sense of and commitment to bridge-building. There’s syncretism and interfaith imagery and art there. Mom[Stanley Ann Dunham] worked as a consultant, building microfinance programs in the Asia-Pacific. I would go with her to these villages where she worked with weavers and tile makers and shadow-puppet makers and blacksmiths. And in these villages she would sit in a circle, and she would become family with many of these artists, and there was this spirit of collaboration that I witnessed.Advertisement

And in 2013, I went to Mount Bromo [in East Java, Indonesia] after the devastating volcanic eruption. They were, as a community, creating microfinance programs because their fields were scorched. They were building each other’s homes. They had built 200 homes for one another voluntarily. Over the course of three years, they were using high-tech solutions to guard against the lahar (mudslides), but also doing all this gorgeous community mapping so that everyone knew their responsibility and would take care of each other. Those lessons are lessons that I have taken with me for the rest of my life, and I’m really dedicated to sharing them.

Q: Your fiction deals with the same subjects, such as peace education and connection in the face of climate catastrophe, that you engage with in your nonprofit and academic careers. Do you see it as a tool to continue that work?

A: It is. And I don’t know that I’m the best at it. But I know that in creating a world and drawing from all that I cannot only see but also imagine, and making meaning in ways that are helpful to me, is an antidote to despair for me. You know, this idea of being able to make meaning of the tough stuff, of sorrow and of difficulty. That’s the whole idea of Peace Studio, that there are so many storytellers, many of them more clever and innovative than me who are out there and who cannot only make meaning for themselves in creative storytelling that draws from both reality and imagination, but can also help us to make meaning and make sense of the world around us.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/style/2023/09/16/obama-sister-childrens-book-peace/