Myrlie Evers-Williams sits in her family’s onetime home in Jackson, Miss., feet from a bullet hole in the wall from June 12, 1963. (Rory Doyle for The Washington Post)

Washington Post June 14th A4 Deneen Brown

JACKSON, Miss. — The violent threats against civil rights leader Medgar Evers from white supremacists in Mississippi were escalating in 1963. The phone at the family’s home in Jackson rang off the hook with hate. Racists had thrown a firebomb through the living room window.

Evers, a fast-rising civil rights leader in Mississippi, had led a successful economic boycott against White businesses in Jackson that refused equal service to Black people. He had gone undercover in overalls to investigate the lynching of Emmett Till.

Evers had just given a televised speech on civil rights. But this was Mississippi, and he knew that his work could get him killed.

So did his wife, Myrlie.

“I knew each and every day when he walked out of these doors, we might not see him again,” Myrlie Evers-Williams, 90, told The Washington Post this month, during an interview at that family home in Jackson.

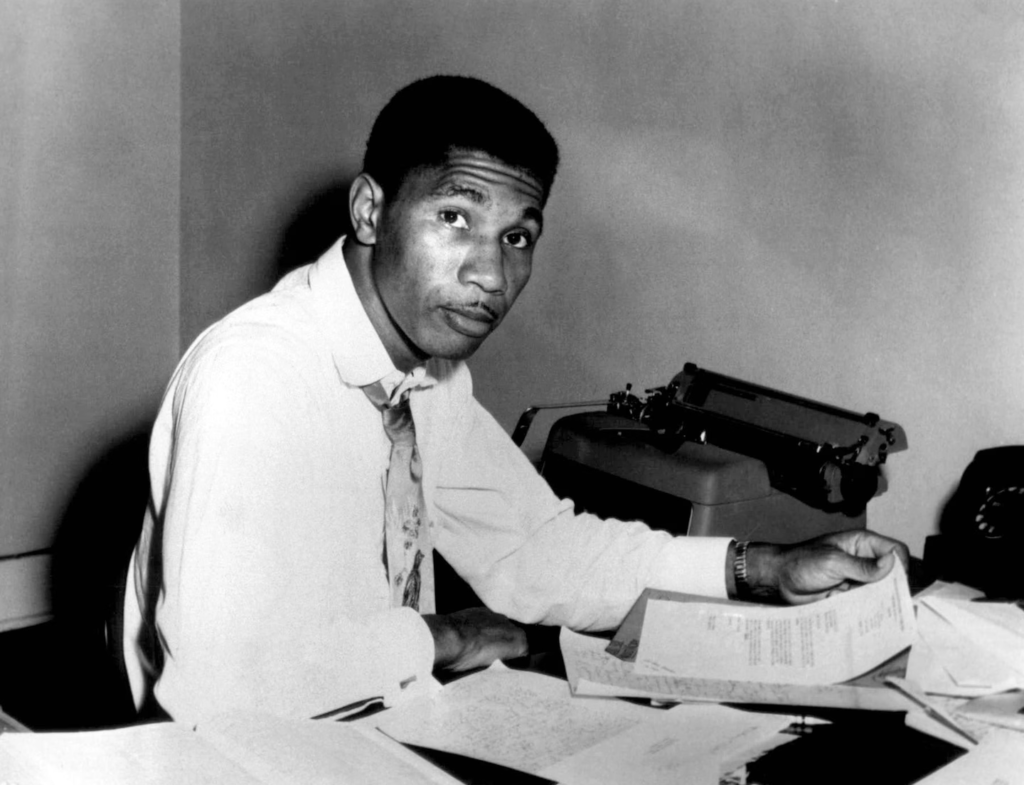

Medgar Evers in August 1955. Evers challenged segregation at the University of Mississippi, then became a leader with the NAACP. (AP)

On June 12, 1963, a white supremacist assassinated Evers in the driveway. He was 37.

Monday’s 60th anniversary of Evers’s assassination comes as hate crimes have increased in the United States, school districts ban books on racism and state legislatures outlaw the teaching of “critical race theory.” Evers-Williams, who herself became a force for civil rights, wants to preserve her late husband’s legacy — and impress upon the country that his work for justice is not done.

“I truly believe there are still problems in terms of race relations,” she said. “As I move around the country, and I do quite a bit, I see the ugliness of it undercover.”

More than ugliness:

“It is an evil. Evil has a way of staying around. Evil has a way of disguising itself, which means those of us have to be watchful, in the best way possible, to work with each other to see that evil does not rise again.”

Who killed Martin Luther King Jr.? His family believes James Earl Ray was framed.

She presses the lace tablecloth on the dining room table in the three-bedroom, one-story rambler. The walls here are painted pale green, the living room window framed by family photos, a black piano and white sheer curtains. Behind her, there are velvet blue sofas and props from the film “Ghosts of Mississippi,” based on the events leading to the final trial of her husband’s assassin.

A bullet from outside pierced the kitchen wall and left a dent in the refrigerator. (Rory Doyle for The Washington Post)

Over her left shoulder is a black-and-white photograph taped to the wall. It’s one the police took that night in 1963. It shows the hole from the bullet that pierced the outside wall of the house and the kitchen wall and left a dent in the refrigerator.

The house, once filled with love, still bears witness to what happened.

The fight of Medgar Evers

Medgar Evers was born in 1925 in Decatur, Miss., the third of five children. When he was about 12 years old, Evers witnessed a Black man named Willie Tingle, a friend of his father’s, being dragged behind a wagon for allegedly insulting a White woman, according to an NAACP report. Tingle was then shot and hanged. A young Evers passed the tree where the lynching happened each day.

When Evers was 17, he enlisted in the Army, fighting in France and Germany in World War II, then returned to Mississippi. When he and his brother Charles attempted to vote in Decatur, a White mob blocked them at gunpoint.

The ‘Mississippi Plan’ to keep Blacks from voting in 1890: ‘We came here to exclude the Negro’

In 1948, Evers enrolled in Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College, where he majored in business administration, was on the debate team, played football, ran track and became editor of the campus newspaper and yearbook. He met fellow student Myrlie Louise Beasley on her first day.

Medgar and Myrlie met at college, married in 1951 and moved to a historically Black town before settling in Jackson. (The Myrlie Evers-Williams Collection at Pomona College)

They married in 1951 and after graduating moved to Mound Bayou, a historically Black town in Mississippi, where Evers worked as an agent for a Black-owned insurance company, selling policies to sharecroppers. He saw firsthand the poverty and despair of Black people who lived in the Mississippi Delta, and organized a boycott against segregated gas stations. “Don’t buy gas where you can’t use the restroom,” read the bumper stickers he passed out.

Determined to gain equal rights for Black people, Evers launched a campaign to desegregate public institutions in Mississippi. In 1954, he applied for admission to the University of Mississippi law school, which rejected him because of his race.P

More on civil rights history

The NAACP national office noticed Evers’s work. That year, the organization named him its first field secretary in Mississippi. He and his family moved to Jackson, where Evers led protests, sit-ins, read-ins and “direct action” to desegregate libraries, buses, beaches, movie theaters, train stations, the state fair and White-owned business on Jackson’s Capitol Street. He led rallies, economic boycotts and drives to register Black voters. He launched a system of “citizenship schools” across the state to help prepare Black voters for literacy tests, to increase those registered to vote. He worked to bring national attention to injustices Black people suffered in Mississippi.

“He would often bring his ideas and plans, most always home, to me to listen to, knowing full well I was shaking in my shoes for his life,” Evers-Williams recalled. “I was born in Mississippi. I knew the state.”

The Everses had bought their home in Jackson from Black developers who were planning a bold experiment in the Deep South: a neighborhood for middle-class Black people, built in the middle of a White suburb.

Evers had designed the house with safety in mind. The front door did not face the street, tucked instead under the carport — providing cover, as he saw it, from potential snipers. When returning home, he would exit the passenger door directly into the side door of the house.

“It took bravery to purchase here,” Evers-Williams said. “It took bravery to move in.”

“I truly believe there are still problems in terms of race relations,” Myrlie Evers-Williams said. (Rory Doyle for The Washington Post)

On May 20, 1963, Evers gave a 17-minute speech on WLBT, a Mississippi news station known for supporting the views of segregationists. He had demanded fair airtime to respond to then-Jackson Mayor Allen Thompson, who had recently given a speech opposing desegregation.

“The Negro has been here in America since 1619, a total of 344 years. He is not going anywhere else; this country is his home,” Evers said. “He wants to do his part to help make his city, state, and nation a better place for everyone, regardless of color and race. Let me appeal to the consciences of many silent, responsible citizens of the White community who know that a victory for democracy in Jackson will be a victory for democracy everywhere.”P

More on Black history

Viewers called in, demanding the station take him off the air. Eight days later, the family’s house was firebombed after Evers organized a sit-in at the F.W. Woolworth lunch counter in Jackson.

The next week, five days before Evers’s death, a driver tried to run him over as he left the NAACP office.

An assassination, and a long search for justice

It was just after midnight on June 12, 1963, when Evers pulled his Oldsmobile into the house’s driveway, just outside the side door where Evers-Williams was sitting 60 years later. He had with him a stack of sweatshirts declaring “Jim Crow Must Go.”

But Evers broke his routine that night: He parked behind his wife’s vehicle, not under the carport, perhaps tired after attending late meetings. He got out of the car on the driver’s side. A White man, who had hid several yards away in a honeysuckle bush, raised a high-caliber rifle and fired.

Medgar Evers was arriving home late when a White supremacist shot him, the bullet passing through Evers and through a window. (Associated Press)

The shot blasted a hole in Evers’s back, passed through his chest and pierced the outside wall of the house. The bullet shot through a kitchen wall, bounced off a refrigerator and landed in a cabinet.

Evers fell near the steps of the house. Inside, Evers-Williams and their three children had stayed awake to watch President John F. Kennedy deliver a major televised speech on civil rights. She “ran for the door,” she recounted to a newspaper later that month, praying “that he was just wounded, that it would not be fatal.”

She opened the door and found the man she calls “the love of my life” lying facedown. Their two older children pulled their baby brother off the bed and crawled to the bathroom, following the safety rules their father had taught them. When they heard their mother scream, they came running back and screamed, too: “Daddy, get up! Please get up!”

MLK’s famous criticism of Malcolm X was a ‘fraud,’ author finds

Across the street, the force of the shot also had injured the shooter when his rifle recoiled. One of the Everses’ neighbors fired a warning shot in the air in response. The shooter dropped the weapon and fled, according to FBI records.

Medgar Evers was pronounced dead at the hospital 50 minutes later, galvanizing civil rights protests across the country.

Myrlie Evers leans down to kiss her late husband’s forehead before the casket was opened for public viewing at a funeral home in Jackson. With her is her brother-in-law Charles Evers. (AP)

Byron De La Beckwith VI, a fertilizer salesman and member of the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens’ Council, an organization developed to support mass resistance to integration of public schools, was arrested 10 days after the murder, connected to fingerprints on the rifle’s scope. According to an FBI report, he “had been asking around to find out the location of Evers’s home for some time before the shooting.

The Ku Klux Klan was dead. The first Hollywood blockbuster revived it.

Twice in 1964, all-White juries deadlocked on the charges against Beckwith.

Men hurl rocks at a line of police blocking an intersection in Jackson on June 15, 1963, as mourners demonstrated following Medgar Evers’s murder. (AP)

In 1989, prosecutors reopened the case, based on evidence published in the Clarion-Ledger newspaper that a secretive, pro-segregation state agency had helped Beckwith’s attorneys screen jurors at trial.

On Feb. 5, 1994, more than 30 years after Evers’s murder, Beckwith was found guilty of it. He was sentenced to life in prison, where he died in 2001.

The rifle he used to kill Medgar Evers went on display at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum.

A family civil rights legacy

The Evers family home is now a museum, too: the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument, run by the National Park Service. So many years later, Evers-Williams can still feel Medgar’s presence inside it.

Evers’s name is ever-present in Jackson: at the airport, a library, a boulevard and murals that loom larger than life — accomplishments attributed to Myrlie, who continued his work.

President John F. Kennedy, center, visits with Myrlie Evers-Williams, left, widow of civil rights leader Medgar Evers. Also pictured: Reena and Darrell Evers, children of Medgar and Myrlie; Charles Evers, far right, brother of Medgar. (Cecil W. Stoughton/White House Photographs/The Myrlie Evers-Williams Collection at Pomona College)

The determined father who took Linda Brown by the hand and made history

Only hours after Evers’s murder, Evers-Williams had gathered the fortitude to lead a mass meeting at Pearl Street AME Church in Jackson, rallying the crowd to continue the fight. She traveled the country thereafter giving speeches on civil rights. A year after the murder, she moved with her children to California, where she eventually ran for Congress and became a commissioner of public works for Los Angeles.

In 1976, she married another civil rights activist, the late Walter Williams. The next year, she was elected chair of the NAACP.

President Barack Obama embraces Myrlie Evers-Williams during her visit in the Oval Office in 2013. Evers-Williams delivered the invocation at Obama’s second inauguration. (Pete Souza/White House Photograph/Myrlie Evers-Williams Collection, Pomona College)

In 2013, Evers-Williams became the first woman and first person who was not a member of the clergy to give the invocation at a presidential inauguration, speaking at President Barack Obama’s second.

This summer may be the last time she visits the house, she said. She pressed the lace tablecloth on the dining room table. She explained how, after what had happened here, she willed herself to go on.

“I certainly didn’t want Medgar to be forgotten overnight,” Evers-Williams said. “I wanted the movement to continue. I didn’t want people to back down, because that would have been a slap in his face. And I felt that is what he would have wanted me to do. For the rest of my life, everything I did was based on what I thought he would have wanted.”

The Evers family home in Jackson, Miss., is now the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument, run by the National Park Service. (Rory Doyle for The Washington Post)