The draft map, which needs to be approved by the county council, includes a district with a Black plurality and another with a Hispanic plurality.

By Rebecca TanYesterday at 6:13 p.m. EDT

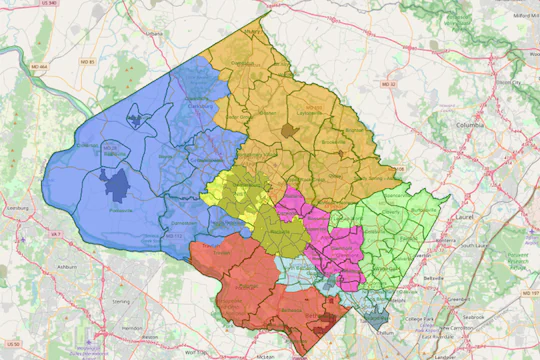

Montgomery County has sketched out a new council district map that reflects the suburb’s surge in Black, Latino and Asian residents over the past decade, and attempts to boost representation for communities in the northern, more rural parts of the county. As decided by a 2020 ballot measure, the map adds two districts to the existing five, creating seven district seats on the County Council on top of the four at-large positions.

The county’s redistricting commission voted 6 to 5 Wednesday evening to submit to the County Council one of three draft maps, which was designed by commissioners David Stein, Keshia Desir and former council member Valerie Ervin (D). The council will hold public hearings before a final approval.

Of the seven districts in the draft map, six have voting-age populations that are majority people of color, a reflection of the dramatic demographic changes recorded in Montgomery’s most recent census results. Since 2011, the last time district lines were redrawn, Montgomery has added about 90,000 new residents, many of them immigrants.

Study: Montgomery County has grown older, more diverse and pricier

One district, in the eastern part of Montgomery bordering Prince George’s County, has a Black plurality; and another, containing parts of Wheaton and Aspen Hill, has a Hispanic plurality. Potomac, Bethesda and Chevy Chase compose one district — the only one with a White majority — and the municipalities of Gaithersburg and Rockville form another. Takoma Park and Silver Spring are carved out of the existing District 5 and grouped with North Bethesda, and the remaining two districts divide the northern parts of the county along the border between Clarksburg and Damascus. The current District 1, which stretches from Poolesville to Bethesda, is split apart.

“This map tells the story of Montgomery County,” said Ervin, who represented District 5 from 2006 to 2014. “Hopefully, an outgrowth of this map is that we’ll see more people running for council seats who we haven’t seen before. … More Latino candidates, more Asian candidates, more Black candidates — that would be the best outcome of all.”

In recent meetings, commissioners debated how to divide districts between the northern, more rural “upcounty” and the southern, more urban “downcounty.”

Commissioners Jason Makstein and Nilmini Rubin voted Wednesday against approving the draft, saying that the way it had been drawn diluted the voices of upcounty residents, who were among the most vocal advocates for additional council seats last year. Clarksburg is split into different districts, as is Travilah, Makstein noted. Rubin said the new map might allow an overrepresentation of the downcounty, noting that all of the council’s at-large members live close to the border with D.C.

Other commissioners, however, said that was irrelevant. People from across the county can run for at-large positions, Ervin noted. Germantown in the north is the most populous census-designated place in Montgomery, and could theoretically elect its own at-large member. But voter turnout in Germantown has traditionally lagged behind other neighborhoods.

Women dominate early field of new candidates for Montgomery County Council

“We are not designing districts based on voter turnout,” commission chair Mariana Cordier said in an interview before the vote. Each of the seven proposed districts have about the same population — 150,000 — and while upcounty has grown more populous over the past decade, so has downcounty, she added.

Marilyn Balcombe, a Germantown resident running in the June 2022 Democratic primary for a district seat, said she understands the frustrations of voters in her area but believes the solution lies more in boosting voter turnout than in redistricting. While at-large council members are meant to represent the entire county, they lack natural familiarity with the experiences of upcounty residents if they live in Takoma Park or Silver Spring, said Balcombe.

“Our needs are different,” she said, citing the example of public transit. “There are a lot of people in the county who would advocate ‘no more roads’ but that just doesn’t work in the upcounty … We don’t live in the street grid, we live in a cul-de-sac.”

Advocates from the county’s predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods celebrated the draft map, which they say will help provide overdue representation to communities that have been disproportionately affected by poverty, joblessness and, more recently, the coronavirus pandemic.

“There’s been over 40 years of nondevelopment in east county,” said Daniel Koroma, a naturalized U.S. citizen from Sierra Leone and civic activist in White Oak. “Having a champion, a dedicated council member for a Black-majority district — it’ll make a huge difference.”

Ervin, the first Black woman to serve on the council, said east county has been the historical home in Montgomery for many Black families who weren’t able to buy homes in other parts of the county because of redlining and other discriminatory practices. “This map will give them the opportunity to elect someone who represents them and their community,” she said. “Our district map has not done that before.”

As of Thursday, 12 candidates had officially filed to run in the Democratic primary for County Council, which in deep-blue Montgomery often determines the eventual winner. Once finalized, the new district map is likely to influence where candidates choose to run.

Council members Andrew Friedson (D-District 1) and Sidney Katz (D-District 3) are running for reelection, while council members Nancy Navarro (D-District 4) and Craig Rice (D-District 2) are term-limited, leaving at least four districts without an incumbent candidate. Council President Tom Hucker (D-District 5) is not term-limited but has said he is weighing a bid for county executive.