In ‘The Anxious Generation,’ Jonathan Haidt argues that the move from ‘play-based childhood’ to ‘phone-based childhood’ has had disastrous effects

Review by Judith WarnerMarch 22, 2024 at 10:29 a.m. EDT Washington Post

If you follow the always abundant literature of What’s Wrong With Today’s Kids, then you’re already familiar with the work of social psychologist Jonathan Haidt.

A professor of ethical leadership at New York University’s Stern School of Business, he’s most widely known for his 2018 bestseller, “The Coddling of the American Mind,” in which he and co-author Greg Lukianoff excoriated the new campus culture of “safe spaces” and “trigger warnings,” and tied the emotional fragility they believed underlay those developments to soaring rates of depression and anxiety in college students.

In the years since, Haidt has been a frequent research and sometime writing collaborator of Jean Twenge, the prolific and controversial psychologist whose Atlantic cover story in 2017, “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?,” set the tone for their work.

Along the way, Haidt has picked up a cadre of haters (the “kids are alright” crowd, he calls them) who have accused him of cherry-picking examples, retrofitting tired old arguments about “kids today,” and stoking “moral panic” about new technology to puff himself up and keep Gen Z down.

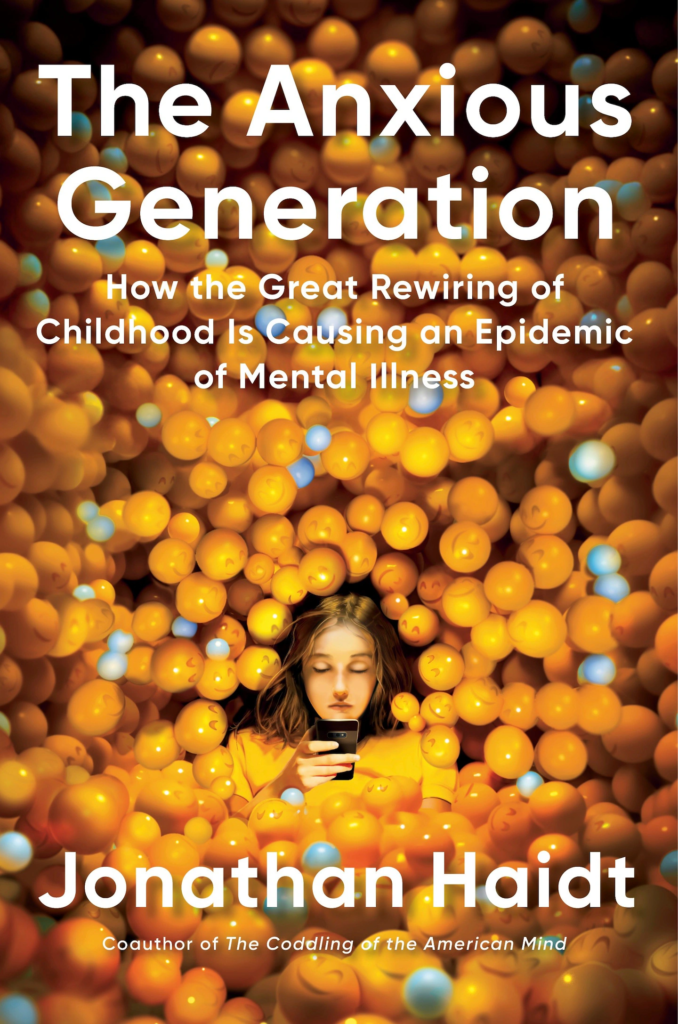

His new book,“The Anxious Generation,”is not going to make his life any easier.

In it, Haidt builds on his previous work and beefs it up, arguing that young people today — specifically those belonging to Gen Z — are damaged products of a massive shift in the culture of childhood. Born in the late 1990s to fearful and overprotective parents, they were raised, unlike the baby boomers and Generation X, with almost constant adult supervision. They became the first-ever cohort of tweens and teens to go through adolescence under the thrall of smartphones, forming their identities in the largely unregulated, ill-understood universe of social media. The toxic combination of “overprotection in the real world and underprotection in the virtual world” (Haidt’s italics) made them super-anxious. Time spent on screens and away from in-person interactions layered in depression-inducing isolation, deprived them of sleep, fragmented their attention, and got them addicted to the dopamine hits of likes, retweets and comments. “Gen Z became the first generation in history to go through puberty with a portal in their pockets that called them away from the people nearby and into an alternative universe that was exciting, addictive, unstable” and “unsuitable for children and adolescents,” Haidt writes.

By his calculations, technological innovation after innovation — “hyper-viralized” social media; front-facing, “selfie”-enabling phone cameras — added up to disaster: a 145 percent increase in depression among teen girls from 2010 to 2021, a 161 percent rise among boys in those same years, with big hikes in anxiety disorders, self-harm and suicide, too. “The Great Rewiring of Childhood, in which the phone-based childhood replaced the play-based childhood, is the major cause of the international epidemic of adolescent mental illness,” Haidt writes. And with that one tricky word, “cause,” he stakes his latest claim — and opens himself up to what’s likely to be a world of pain.

Even if you question the specifics of how Haidt slices and dices his data (and I do, up to a point: to generate those showstopping depression numbers, for example, he includes data from 2020 and 2021 — years of off-the-charts stress due to the onset of the pandemic, during which data collection methods dramatically changed), there’s no doubt that young people today are in the throes of a mental health crisis that’s unprecedented in scope and severity. The latest statistics are terrible: According to the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, for example, almost 1 in 5 of 12- to 17-year-olds had a major depressive episode in the past year, while nearly half of 18- to 25-year-olds had either a substance use disorder or a mental illness.

But proving causation (rather than mere correlation) is an iffy proposition. It’s especially risky for Haidt in the face of a large body of scholarly literature on the psychological harms of social media that’s ambiguous at best.

He acknowledges this, and tries to get around the problem with the sheer amount of correlational evidence he pools together and combines with laboratory experiments he ran with Twenge. He also gives himself a convenient out, saying he “will surely be wrong on some points”; he’s even set up a research site that he will maintain, inviting other researchers to weigh in.Share this articleNo subscription required to readShare

That’s all well and good — clever marketing, for sure — but unfortunate for the book as a reading experience. For one thing, in assiduously working to prove quantitatively his very likely unprovable “Great Rewiring” hypothesis, Haidt spends the first two-thirds of the book writing defensively, as if speaking to an audience of straw-man detractors just waiting to score a gotcha against him. This results in a lot of artless rigidity: too much repetition, refining and redefining of dates and definitions.

Haidt’s investment in his “Great Rewiring” theory also leaves him with some blind spots. His call for anxious adults to let kids roam assumes that all overprotective parents live in areas that are basically safe, where kids can bike around or run errands or go house to house to play without, say, having to cross a six-lane highway. He misses the mark when he writes of Gen X parents “gleefully and gratefully” recalling their childhood independence; the kind of loud laughter he hears when he raises the topic, in my experience, is often more angry than nostalgic, children of the 1970s parenting as they do in reaction to the emotional absenteeism of their own parents. And his recollection of free and fun suburban childhood overlooks the fact that growing up is brutal for many — above all for kids who don’t fit the norms that prevail in their communities. To mock, as Haidt does, a playground sign at an elementary school in Berkeley, Calif., that includes “Tag Rules” like “Include everyone,” “No ball tag” and “If a player doesn’t want to play tag, then other players must respect that,” is to ignore that when children “manage their own affairs,” it’s often a “Lord of the Flies”-like experience.

Haidt also minimizes to the point of outright dismissal the sick-making potential of the unabating storm of miseries that Gen Z has endured in its not-terribly-long life span: 9/11 and its fearful fallout, the Great Recession, the climate crisis, hundreds of school shootings, crushing student loan debt, increased economic inequality, the opioid epidemic, and the spike in words and acts of hate targeting nearly every vulnerable group in turn. All are toxic stressors, and in the 2010s, all acted upon kids’ nervous systems, affecting them to different degrees, depending on their life experiences and their genetic propensity for mental illness.

Haidt could have done a lot with all that material. Because, when he steps away from his data — when he writes, as he puts it, “less as a social scientist than as a fellow human being” — his book can be quite wonderful. His chapter about the “spiritual degradation” of the phone-based life for all of us, regardless of age, beautifully grounds his critique in Buddhist, Taoist and Christian thought traditions. There’s no quibbling with Haidt’s suggestion, borrowing a phrase from the Tao Te Ching, that most of social media is “dust on the pedestal of the spirit.” His common-sense recommendations for actions that parents, schools, governments and tech companies can take (I should say “ought to take” in the case of governments and tech companies, because they won’t) are excellent. They include putting phones away in special pouches or lockers during the school day; keeping smartphones out of the hands of kids before high school (“basic” phones without internet connections are fine); and keeping younger kids off social media by raising the threshold for “Internet adulthood” (when a kid can sign a contract with a company to give away their data and some of their rights) from the current ridiculous age of 13 to 16, while also instituting enforceable methods for age verification.

There are a couple of big-picture questions Haidt doesn’t ask, much less answer: How did we end up putting electronic devices in the hands of children for hours on end in the first place? Why were we so collectively admiring of the “heroes, geniuses, and global benefactors” of Silicon Valley, who by their own admission sociopathically exploited “a vulnerability in human psychology,” as Sean Parker, the first president of Facebook, put it — our hard-wired need for connection, validation and approval, especially acute in middle-schoolers — to hook us in and screw us over, at younger and younger ages?

I can’t help but think that online childhood is less a cause than a symptom of a society-wide mental pathology that has swallowed up adults and kids alike. It may be that the multiply layered traumas of recent years have pushed us past a tipping point. In the epidemic of mental illness in kids, we may really be seeing what it looks like when vulnerable people are “triggered.”

Judith Warner’s most recent book is “And Then They Stopped Talking to Me: Making Sense of Middle School.”